John Rawlings, his Mechano set and Chinese Junk

John Rawlings, his Mecano Model and his Chinese Junk

By Phil Pressel and Paul Brickmeier

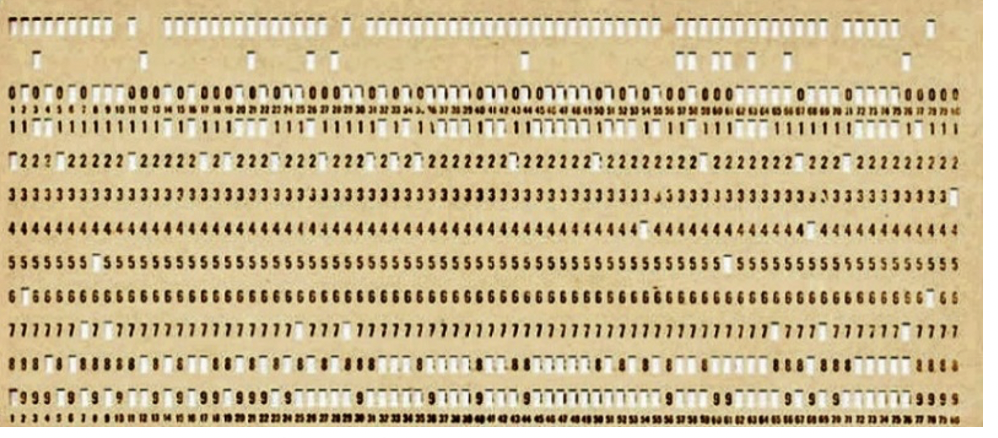

John Rawlings was a Brit and a tinkerer. He loved to make models with his Mecano set. He also made cardboard pendulum clocks that actually worked. He was chartered with the design of an actual model of the Hexagon camera system at the beginning of the program.

He had the Mecano room with 4 or 5 designers and that was an army working on the model. Paul Brickmeier was the project engineer responsible for the design of the actual flight film supply assembly and had only 1 designer to work on what was supposed to be the baseline design. He remembers getting fairly discouraged.

I (Paul) was in Mike Maguire’s office one day (Mike was the Director of the Hexagon program) and he said, “what can I do for you.” I said “you can stop that Mechano effort; I can’t keep the few people that I have on the design motivated because they were convinced that Rawlings was going to win out completing the model.” So, he looks me in the eye and says, “never gonna happen but I can’t change it because Ken Patrick, (a VP at the time) was championing this thing, but it won’t happen.”

A short time later Mike calls me into a meeting with Don Patterson (the CIA chief of the program), Paul Convertito (manager of Systems Engineering), Besserer of TRW (consultants to the CIA) and the whole nine yards are there. It was a high-level meeting with VP’s of Perkin Elmer and whoever. We were there to back up Mike and to sit on the sidelines. I always remember this meeting because the Vice Presidents of this world weren’t in the same league with the head honchos of this program, but Maguire was and he stood out in that crowd as being equal and they treated him as an equal in this environment. They get to this thing on the film take-ups and Besserer says “what have we got John doing?” and someone says we have him working on the take-ups acting as the carrier for the film. And everyone in the room started laughing and they said, “it’s time to kill that.”

The next question was “what do we have John do next?” They considered him an inventor resource; they said we’ve always had problems with cut and splice methods, let’s put him on that. The meeting ended and the first thing the next morning I come in and the Mecano room is being taken apart and the guys are being re-assigned off somewhere and I thought John would be down. He’s not down, he’s happy as a clam. He said “wow we’re gonna cut and splice.” He was a terrific creative enthusiastic guy.

He did eventually design and build a motorized scale model of close to the actual Hexagon camera system and even put in a coin machine so that people had to put a quarter in to see it operate. He even made Chester Nimitz our President and CEO put money in.

The only thing he wasn’t too smart about was that crazy Chinese Junk boat he had.

Mike Krim remembers being invited to go out on the Junk with John with Dick Babish and all. When they got to the marina all they could see was the mast sticking out of the water. It had sunk. And John, as a master of understatement said, “oh my.” He did take a bunch of us out to sail on Long Island sound. I, Phil Pressel and a few of the other mechanical engineers did go out successfully once on his Junk. John was a real character.

John’s Chinese Junk